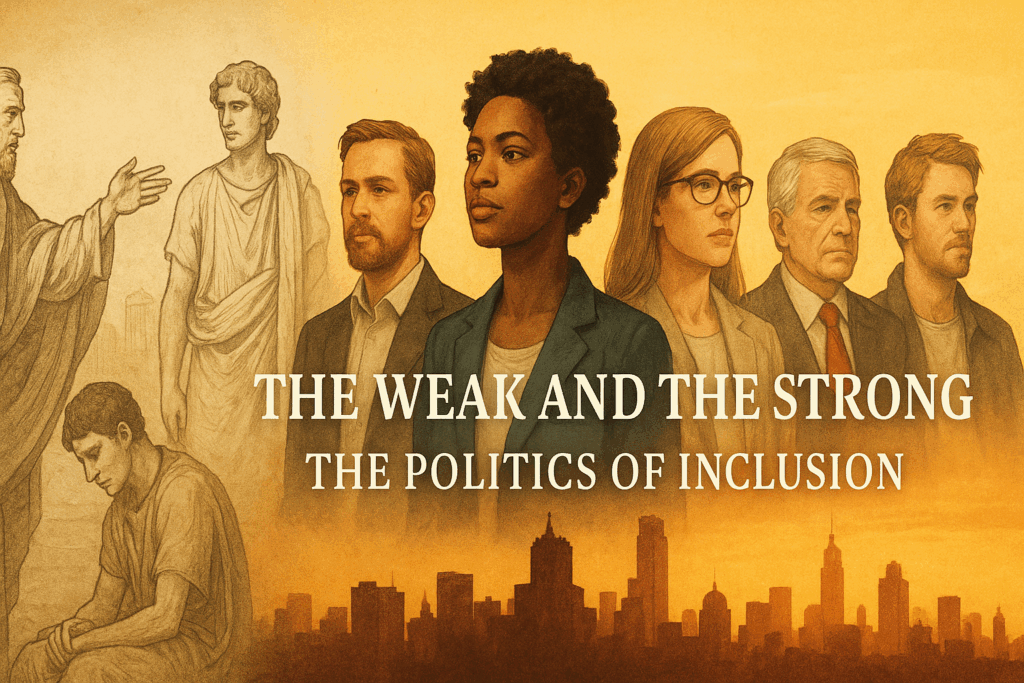

Few ideas have shaped modern pluralistic society more than the principle of tolerance. At the heart of Paul’s teaching lies a remarkable ethic: the strong are called to limit their liberty out of love for the weak. Freedom is never an excuse for disregard; instead, it is bounded by responsibility toward others. This Pauline paradigm is foundational to the politics of tolerance, setting the stage for modern democratic life, where diverse consciences and convictions must coexist in mutual respect.

The Scriptural Witness

Paul addresses the question of differing consciences in Romans 14:1: “Him that is weak in the faith receive ye, but not to doubtful disputations.” The community is commanded to welcome those of weaker conscience, not for the purpose of endless debate or exclusion. Here, Paul establishes a principle of acceptance across differences. Rather than demanding uniformity, the church is called to hospitality and patience. This marks the seed of tolerance as a virtue—an acknowledgment that unity is not the same as uniformity.

The Apostle develops the theme further in Romans 14:20: “For meat destroy not the work of God. All things indeed are pure; but it is evil for that man who eateth with offence.” Freedom is affirmed—“all things are pure”—yet liberty must be restrained where it causes harm. The true offense is not the food itself but the insensitivity that disregards another’s conscience. This ethic of voluntary restraint is not coercion by law but responsibility born of love. It is the moral logic behind the idea that individual rights must be balanced with the common good.

Paul illustrates this ethic vividly in 1 Corinthians 8:13: “Wherefore, if meat make my brother to offend, I will eat no flesh while the world standeth, lest I make my brother to offend.” Paul himself is willing to forgo legitimate freedoms for the sake of others. This self-limitation is not weakness but strength—a conscious choice to value community over personal preference. It anticipates modern ideas of civic virtue, where citizens accept limits on their freedoms in order to preserve peace, order, and respect for diversity.

The Pauline Paradigm and Modern Ethics

Paul’s teaching that the strong must limit their liberty for the sake of the weak profoundly shaped the moral imagination of the West. At its core is a recognition that freedom without love degenerates into tyranny of the strong over the weak. True liberty is tempered by responsibility to the community. This insight remains central to modern ethics, where rights are paired with duties, and freedoms are exercised with respect for others.

The Pauline ethic also laid the foundation for religious tolerance. Rather than enforcing uniform practice, Paul insisted on mutual respect for differing consciences. This principle, nurtured within Christian communities, would later influence the development of religious liberty in the Reformation and Enlightenment, eventually becoming enshrined in constitutions and declarations of human rights. The ability of diverse beliefs to coexist within one society is not merely a pragmatic arrangement but a direct inheritance of Paul’s vision.

Furthermore, Paul’s emphasis on voluntary restraint anticipates the moral logic of democratic pluralism. In a society where competing convictions must live side by side, the stability of the whole depends on citizens who choose tolerance over domination. Paul’s insistence that the strong adapt themselves for the sake of the weak anticipates the modern ethic of compromise, without which free societies cannot endure.

Why It Matters Today

The politics of tolerance is fragile. In an age marked by polarization, Paul’s paradigm reminds us that liberty is not absolute but relational. The strong—those with influence, resources, or power—are called to use their strength not for self-indulgence but to build up the community. Tolerance is not weakness; it is the strength to limit oneself for the sake of peace.

Modern secular ethics—whether in the sphere of free speech, religious liberty, or democratic coexistence—are deeply indebted to Paul’s teaching on the weak and the strong. The idea that we should protect the conscience of the minority, even at cost to majority preferences, is rooted in this Pauline vision. To forget these roots is to risk losing the moral framework that makes tolerance meaningful, reducing it to mere indifference or coercion.

Paul’s ethic calls us back to a vision of freedom bound by love. It insists that tolerance is not the abandonment of truth but the recognition that truth itself demands patience, humility, and care for the other. This Pauline paradigm remains essential for preserving the pluralistic world we inhabit today.

Memorize The Scriptures And Doctrines From This Pauline Paradigm Here